Dive Into Decarbonization at UC Davis

How 3 UC Campuses are Phasing Out Fossil Fuels

This article, published on Dateline, features excerpts from a recent UC feature story

As each University of California campus prepares to publish its long-term plan for eliminating carbon emissions and transitioning to renewable energy, a new UC feature story shares how sustainability experts on three campuses — Davis, Berkeley and Santa Cruz —are phasing out fossil fuels ahead of schedule.

Each of these campuses has different challenges and considerations as they transition to renewable energy, but they have a few important things in common: committed leaders building teams who embrace the challenge, staff and faculty with deep expertise in engineering, climate science, sustainability and social transformation, and an energized community of activists pushing for urgent change.

UC Davis makes a Big Shift

At UC Davis, the transition to green energy is already well underway. A year ago, crews finished the first phase of what’s known around Davis as the Big Shift, replacing the campus’s natural gas-fired steam apparatus with a system that can use electricity to generate hot water instead. During two years of construction, crews dug great big trenches through the heart of campus, laying four miles of new pipe and swapping out steam heating systems with those that run on hot water in 31 buildings.

For the time being, Davis is burning fossil fuels to heat the water that’s running through the new pipes. But once all the buildings that are connected to this centralized heating and cooling system have been retrofitted, they’ll be able to shut down the natural gas-powered boilers and run the whole system on electric heat pumps. Altogether, the project will shrink Davis’ carbon footprint by 80 percent.

Altogether, the project will shrink Davis’ carbon footprint by 80 percent.

Davis leads UC campuses in decarbonization today in part because this transition has been in the works for 15 years, said Joshua Morejohn, Davis’s executive director of utilities and engineering.

Back in the aughts, “our steam system was 50 years old and going to need to be renewed,” Morejohn explained. In studying alternatives, they found that sticking with steam, which is volatile, expensive and inefficient, was actually going to cost the campus way more money in the long run.

“We cobbled together all the near-term steam projects in the budget, which got us about $50 million. So we said, ‘Let's spend that $50 million on the first phase of a hot-water system that could eventually run on zero-carbon energy,’” Morejohn said.

Decarbonizing UC — not to mention the rest of our economy — in time to avoid complete climate catastrophe is going to take a lot of these kind of “big cultural shifts,” says Ellen Vaughan, assistant director of sustainability for operational and strategic initiatives at UC Santa Cruz.

“You might be able to find 90 percent of the cost of an electrification project in the budget that’s already been allocated for fossil fuel infrastructure replacement. You just need to realize and be excited about the fact there is an opportunity to electrify, and that you don’t have to replace a natural gas boiler with another natural gas boiler.”

How decarbonization supports teaching, research and public service

The three UC campuses leading the green transition have drawn on the collective brainpower of thousands of students and faculty to generate the most efficient, effective and equitable solutions for each campus. Along the way, they’ve generated valuable new scientific insights while providing hands-on educational opportunities for the next generation of climate leaders.

“Climate change is totally an interdisciplinary problem, so it makes sense that we’d go after it with multidisciplinary groups,” said Kurt Kornbluth, assistant professor of biological and agricultural engineering at UC Davis.

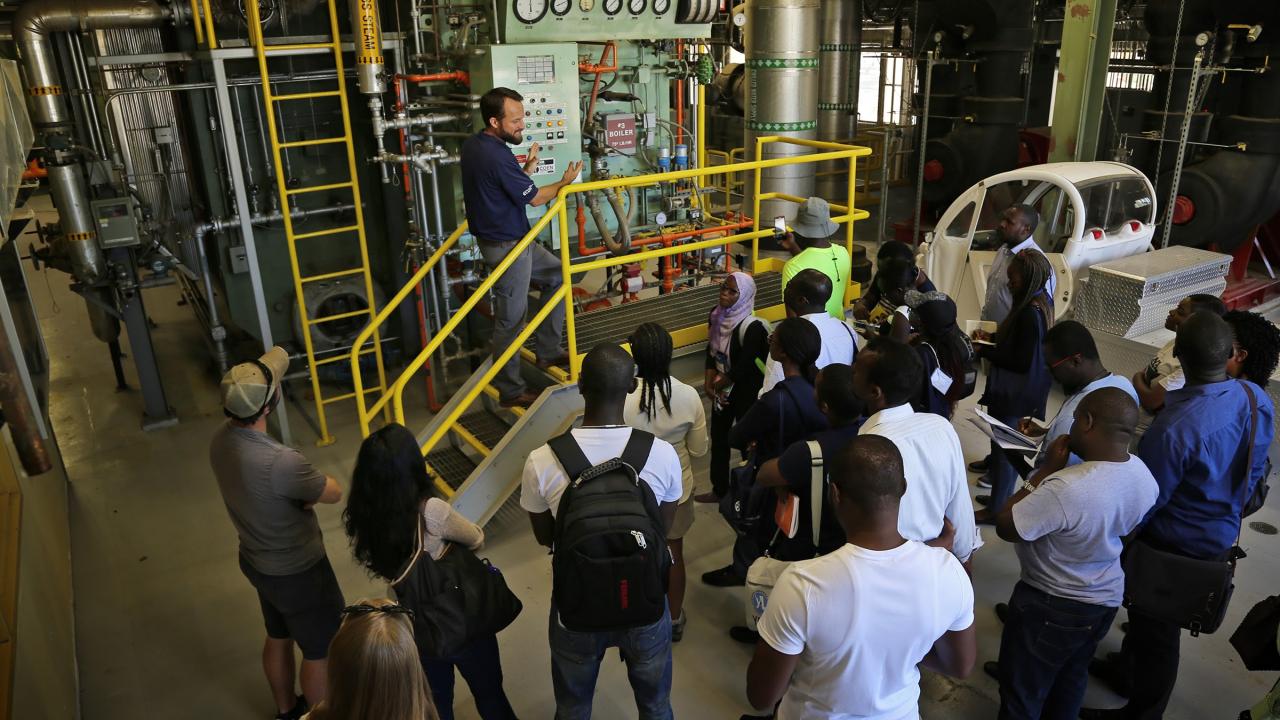

For the past dozen years, he and Morejohn have co-taught a project-based class called Path to Zero Net Energy. Students with backgrounds in everything from engineering to classics have worked together to audit campus building energy use, generate new algorithms for managing water use on campus and even develop the business case that Davis is using to fund the transition from steam to hot water and climate-warming fossil fuels to renewably generated electricity.

Kornbluth and Morejohn also co-lead a campus-backed initiative called Sustainable Campus Sustainable Cities, which casts UC Davis as a living lab for research and education focused on eliminating UC Davis’s carbon emissions. Each year, the initiative hosts a workshop connecting sustainability leaders at colleges and universities around the world.

“On a lot of these issues, our students are the ones doing the consulting for the campus, instead of us having to hire someone from outside. I can use these projects as a springboard for my own research as a professor. And students are getting amazing experience, and they all get great jobs after graduation,” Kornbluth said. “The faculty benefits, the students benefit, and the campus benefits.”